1. The Shoulder

I was eleven.

We were playing the toughest team in our division and I wanted to send the message that we couldn’t be bullied.

I charged down the ice after one of their defensemen. He was stickhandling the puck as he skated backwards along the boards near his team’s bench. His head was up scanning the ice to make a play.

He passed the puck up ice and I took two more strides to finish my hit. As I was about to make contact, the player I was trying to flatten stepped off the ice. Skating at full speed, my right shoulder hit the inside of the boards where the bench door opens. Pain shot through my entire shoulder as if every nerve ending was being scorched by a blowtorch.

With adrenaline masking the pain as my right arm dangled uselessly at my side, I skated off the ice and into the dressing room. Unable to play the rest of the game, I gritted my teeth to distract myself from the pain and took off my equipment with my left hand. I sat in grimacing silence and waited for the game to finish.

Because the puck had been passed away seconds before and the awkward angle of where it occurred on the ice, no one saw my injury happen. When I left the ice, my face was clenched holding back tears but no one knew why. And physically, because my sprain was invisible, I looked fine.

After the game in the dressing room, I sat there trying to display with low moans and a scrunched-up face how badly I was injured as another player on my team, who broke his collar bone that game, got a shoutout from the coach and a round of applause from the team for his physical play and sacrifice.

My injury went unrecognized.

As the hospital later confirmed, my shoulder was sprained so badly that the nurse who took my X-ray tried to convince me that hitting shouldn’t be allowed in hockey. I couldn’t move my arm a centimetre in any direction without a spiderweb of pain spreading through my shoulder.

For the next few weeks, my hand was effectively glued to my pocket—the only position that wasn’t unbearably painful—as my shoulder healed.

2. The Arm

A month after fully recovering from my shoulder sprain, I was tobogganing on an out-of-use green-rated ski hill in a valley close to our house with my mom and brother.

The hill was the length of a stretched-out Olympic track and declined so steeply—steep enough to have taken someone’s life from a head injury years before—most kids started their sled runs only halfway up.

I finally mustered the courage to go from the very top where the ski lift used to drop skiers. I jumped on my toboggan and barrelled down the hill at a speed that turned the alpines on either side of me into one continuous forest-green streak.

Halfway down, I accidentally hit a jump made of packed snow that had turned into hard, slick ice. I caught a few feet of air and my sled shot out from under me as I came crashing down on my left arm with a snap.

Unlike the shoulder sprain, I didn’t feel any sharp pain. But something felt off. I sat out as my brother took a few more runs.

By the time my mom peeled off my coat to see what my complaints were about, my arm below my elbow was purple and closer in shape to a half-circle than a straight line.

The triage nurse at the hospital, struggling to hide her panic, took one look at my arm, shot up from her desk, and rushed me to the back of the hospital for emergency surgery. If my arm wasn’t reset immediately, the lack of circulation could have starved my arm’s muscle cells of oxygen for too long leading to permanent loss of function.

My mom couldn’t bear it but my dad watched the surgery through a small glass window in the operating room door. Two nurses held my limp unconscious body down as the doctor hauled on my broken arm as if he was in the most intense match of tug-of-war in his life. Eventually, the broken bone snapped back into alignment.

Even though my arm was broken below the elbow, I drowsily woke from anesthesia with a heavy L-shaped plaster cast that stretched from my knuckles to my armpit. I would argue that the cast was more effective at ensuring I didn’t sleep than healing my arm.

After a week, the plaster cast was replaced with a lime-green fibreglass cast of the same shape. A few weeks after that, I was able to bend my arm again as my third cast, hot-pink fibreglass, stopped at the cup of my inner elbow.

The most painful part of breaking my arm, which rivalled my shoulder sprain, was the overly aggressive physiotherapist who insisted on taking my wrist through its full range of motion not five minutes after my arm was permanently relieved from its cast.

For the last month and a half, my wrist was locked in a fixed position. He sat in a chair beside me in the hallway outside the room in which my cast was just sawn off and forcefully, through my wincing protests, bent my wrist up, down, left, right.

*

My sprained shoulder and broken arm led me to miss most of that hockey season.

When I returned for the final few games, I played horribly. As soon as I touched the puck I’d fire it down the ice so I couldn’t get hit or make a pass that got intercepted by the other team. I stopped scoring, shied away from puck battles in the corner, and avoided physical contact.

No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t go back to playing like I did before my first injury.

I was letting my team down. I hung my head in shame and dreaded car rides home because of how embarrassed I was of my performance. My mind was paralyzed with fear and I couldn’t force myself to relax and play. Showering after games, I averted the mirror’s gaze so the word that had been ricocheting off the insides of my skull couldn’t shoot out my eyes and land on me: coward.

That was my last season of competitive hockey.

The next year, I decided to drop down to recreational hockey where hitting isn’t allowed and play competitive soccer instead.

3. High School Days

I spent my high school years fighting the feeling that I was a coward.

Before my injuries, I played physically and never hesitated. I was blissfully ignorant of the possibility of injury. But being injured twice in the same year opened my young eyes and developing brain to the risks of high-impact activities. So much pain. Too quickly and unexpectedly. Followed by months of immobilizing recovery.

Because those injuries happened when I was 11, they became formative experiences that shaped me. Subconsciously, the fear of injury stayed with me. I felt it as soon as I stepped on the ice for my first game back after my arm healed during that last season of competitive hockey.

I tried to beat the feeling down, but I was scared to engage in contact sports and physical activities. I felt like I was carrying a secret, ashamed of myself and terrified of others finding out I was timid in the face of physical contact.

*

But I refused to accept that I was a coward. So I built an outer life to prove that I wasn't.

I joined the football team in Grade 10 and played every minute of every game: offence, defence, and special teams. I joined the rugby team in Grades 11 and 12 and played every minute there too.

I didn’t choose to play those sports because I thought they would be fun.

On the love-hate spectrum, I was much closer to hating every second of every game and practice than loving them. I forced myself to play football and rugby, two of the most physical sports there are, to fight the fear that I had become a hesitative coward. I was on a quest to prove my courage to myself.

I pushed through and mustered as much aggression and physicality as I could.

In rugby games, I wanted to make as many hits and get as many touches on the ball as possible. I wasn’t a good tackler, but on defence, I forced myself to put my body in front of the other team’s ball carrier. I cared more about proving to myself that I wasn’t scared to get physical than whether we won the game.

But no matter how hard I tried to play, I felt threatened by every other player on the field. During kickoffs in rugby, I prayed the ball wouldn’t land in my zone because I knew that the second I jumped up and caught the ball, another player would run me over. I was big and strong, standing over six feet tall and 195 pounds of lean muscle, but felt soft inside.

A voice in my head kept whispering that I was a coward wearing a mask of courage. And I was convinced that my teammates and coaches knew it.

Those voices were still raging when I graduated. They weren’t done with me yet.

4. Sparring

Once I got to university, I was safe from playing contact sports.

But the fear that I was a coward only buried deeper within me because I no longer had an outlet, that football and rugby provided in high school, to prove myself wrong.

As the years passed and I gained more distance from high school, layers of time stacked upon each other like skin growing over an open wound. On the surface, I thought the self-assurance I was supposed to gain in adulthood had healed the injury-shaped hole in my psyche.

But below the surface, an infection festered.

I had tried to stitch over a wound—the deep-seated feeling I was a coward—without gritting my teeth at the sting of the disinfectant: the hard work I needed to do to repair my relationship with myself. In journal entries, bad dreams, and, worst of all, each time I met a varsity athlete or martial arts competitor, I was reminded of my inadequacy.

The same questions kept coming back to me:

Are you a coward? Are you scared of physicality?

To prove to myself that I wasn’t, I had to get physical.

So in the Summer of 2022, nine months after graduating from university, I joined a Krav Maga gym. Krav Maga is a self-defence martial art derived from a combination of other fighting techniques. I quickly began attending every class on the schedule, training for eight to ten hours a week, plus runs and workouts on my own time.

With each Krav class, I started to feel healing.

I felt my inhibition towards physicality fade with each punch, kick, elbow, knee, and choke I took and delivered. The timidness that had prevented me from bonding with my high school football and rugby teammates melted away. Through beating each other up, I became friends with my Krav classmates.

For the first time since I was eleven, I didn’t feel scared in physical contact. I wasn’t just getting physical, I was enjoying it. In football and rugby, I pretended to be tough. But in Krav, I started to feel deep in the spongy marrow that fills the cavities of my bones that I was courageous in the face of physicality.

Then my instructor cleared me to start attending sparring sessions.

*

Unlike the technique and striking classes I had been attending, which consisted of violent but controlled drills, sparring is uncontrolled one-on-one fighting.

Sitting on the dock at my family’s cottage on the weekend, looking out at a bright blue sunny sky and glass-like lake, my head was a warzone preparing for Monday’s sparring session.

The tension in my mind was so unbearable that even a crow squawking in the trees would set me off in a mumbling fit of restless rage: “God damn crows are so loud around here.” I felt the same Sunday dread for sparring classes that I used to feel when I worked twelve-plus hour days in accounting with an hour-long commute each way.

The courage I had started to feel was washed away like the sand on a tide being sucked out to sea.

I was familiar with this feeling. I had felt it in high school when I played football and rugby. And I had felt it when I first started attending Krav classes a month earlier. I knew there was only one way to fight my feelings of cowardice: Go to every single sparring class. Drop my ego. Get beat to a pulp. Keep coming back.

So I did.

I didn’t miss one sparring session. My fears of physicality disappeared with the first punch I threw. Hour-long sparring classes passed in what felt like ten minutes.

5. The Man In The Arena

On the bike ride home from three hours of Krav classes and sparring one Toronto summer night, I passed patios and parks full of young people eating, drinking, and laughing.

Then it hit me: I had never been a coward. Not in high school and not now.

Cowardice is opting to sit on the sidelines because of fear.

Courage isn’t playing without fear, it’s playing despite fear.

Although I felt fearful and timid, I always took action. I joined the football and rugby teams when I could have easily stuck to soccer. No one knew the internal battle I was fighting but me. And I showed up to fight that battle every day as courageously as I could.

It’s a battle I will never stop fighting.

By Autumn, I plan to land a job, move from the country back into a city, and start training BJJ.1 I know I’ll feel the same fear and hesitation some days, especially when I start sparring with guys who could choke me unconscious or break my arm before I know what’s happening to me.

But I will show up nonetheless.

Because the only way through fear is to plant my feet firmly in the arena.

With love,

Thank you

for multiple rounds of incredibly helpful feedback on this essay.Subscribe for new stories every Thursday:

Quote I’m pondering:

Frank Herbert in Dune:

“I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration. I will face my fear. I will permit it to pass over me and through me. And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path. Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain.”

Chills. This may be my favourite quote of all time.

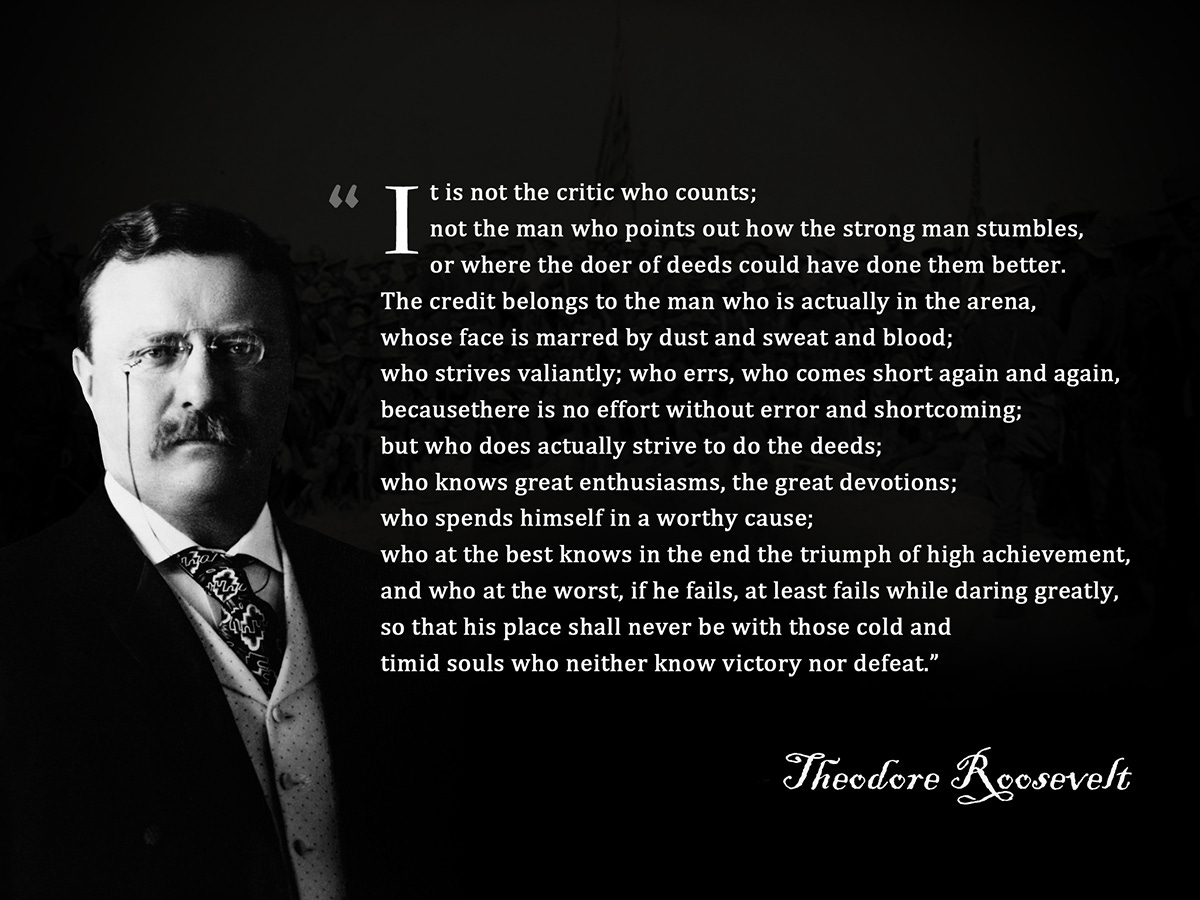

The Man In The Arena

In Paris on April 23, 1910, the 26th U.S. President, Theodore Roosevelt, gave a speech titled "Citizenship In A Republic."

One section of that speech, The Man In The Arena, is famously remembered.

The last week:

Thanks for reading!

1 — Leave a like. I’d be grateful if you’d consider tapping the “heart” ❤️ at the top or bottom of this page.

2 — Let’s chat. If you want to share your thoughts, please leave a comment on this post. I’d love to hear from you and I respond to everyone!

3 — Share the love. If you know someone who may enjoy reading this, please share it with them.

P.S. If you want to reach me directly, please respond to this email or message me on Substack Chat.

“Cowardice is opting to sit on the sidelines because of fear. Courage isn’t playing without fear, it’s playing despite fear.” Such a powerful realization. Substitute “playing” for “living” and this is also so true. You live with courage. You have self-assessed this 11 year olds fear, challenged it and have come to understanding its power over you, courageously conquering the very thing you “feared” the most. All the while learning a little more about yourself. Beautiful!!

Loved this piece Jack and to watch your evolution as you continually to deepen into your storytelling. Especially on how the fight must continue to be fought — courage isn’t some fixed result but this continuous process of showing up. Again and again.

Way to go on this piece (: