Every two weeks, I drive thirty minutes into town from my family’s rural cottage to grab groceries and do laundry. While waiting for my laundry during my last visit, I strolled across the street to a country market.

Stacked high in a big bin near the front of the store sat just-delivered Spanish peaches.

I bought one and walked back across the street to eat it. Standing outside the laundromat while revelling in the splendour of the hundred-year-old church next door, I took a bite of my peach.

Firm but not hard. Tart but not tangy. Sweet but not sugary. Juicy but not drippy. It was the most delicious peach I ever tasted.

In an architectural trance at the church, as my tastebuds watered for more peach, my thoughts drifted to how the Spanish peach made it to my hand in rural Ontario.

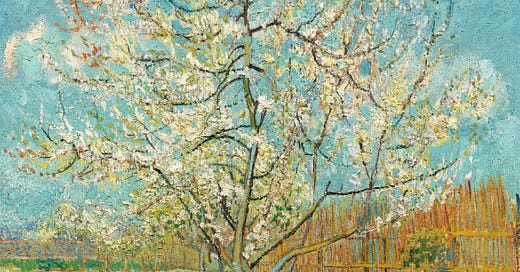

A Spanish farmer, whom I’ve never met and whose language I don’t speak, planted the peach tree, from which my peach grew, on his land at least three or four years ago.1

In the months during which my peach transformed from a hard green ball to ripened fruit, he fought moths, bugs, aphids, rodents, caterpillars, worms, and nymphs to keep the tree alive and the fruit unvandalized by hungry pests. All without the help of pesticides to maintain his organic status.

He rose early, toiled ceaselessly, and sweated under the Spanish sun to sanitize, prune, thin, and eventually harvest his peaches, ensuring his crop was delivered in top condition so he could make his living and bring back repeat customers next year.2

As I chewed on the next bite of peach, I remembered the Colombian banana farmers I watched work for a few moments in passing on a hike in Colombia two years earlier.

One man used a machete to cut down bunches of at least fifty bananas. He tossed them to another man who caught and stacked them. As they tirelessly worked, unshaded from the midday sun, I thought of the deadly Brazilian wandering spider that lurks in banana trees. Bananas sold for less than $2 a bunch in Canada. Those men were risking their lives for pennies.

*

You and I live in a neverending river of abundance.

But many around the globe still live today in what was the natural human condition up until the last eighty years: extreme scarcity.

The case for saying grace isn’t a religious one.

Humans lived in harsh scarcity for nearly all of our existence. Having an abundance of food is an extremely new phenomenon.

A short grace is a way of being thankful that we live in a time and place of plenty. It’s a way to recognize that our food has been provided by a farmer in a faraway land who worked very hard for months to grow what we nourish ourselves with.

Food doesn’t appear on shelves in bottomless supply without hard work and sacrifice.

Saying grace gives recognition that life died for food to appear on our plates. Life had to be sacrificed to produce meat. And in tending to and ploughing the fields of wheat, corn, potato, and other crops that makeup so much of our diet, mice, rats, birds, rabbits, frogs, lizards, moles, possums, snakes, and insects are killed.

Then by some staggeringly sophisticated supply chain, food travels around the world to a nearby store where we buy it with no effort, other than the effort we put into our jobs to earn money. Yet punching at a keyboard all day is a hairline fraction of the amount of effort it takes to grow food.

Pausing for a moment to be grateful before taking the first bite is a thank you to the animals that died, the farmers that worked, and the supply chain that delivered us our food.

With love,

Thanks to

for planting the seed for this essay in my head by bringing a practice of grace to our dinner table. And to for your wise, thoughtful, and helpful edits on an early draft of this piece.Subscribe for new essays every Thursday:

Quote I’m pondering:

Winston Churchill’s first speech as Prime Minister on blood, toil, tears, and sweat (13 May 1940):

“I would say to the House, as I said to those who have joined this Government, I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat. We have before us an ordeal of the most grievous kind. We have before us many long months of toil and struggle.

You ask what is our policy. I will say, it is to wage war with all our might, with all the strength that God can give us, to wage war against a monstrous tyranny never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalogue of human crime.

You ask what is our aim? I can answer in one word: Victory. Victory at all costs. Victory in spite of all terror. Victory however long and hard the road may be. For without victory there is no survival.”

Thanks for reading!

1 — Leave a like. I’d be grateful if you’d consider tapping the “heart” ❤️ at the top or bottom of this page.

2 — Let’s chat. If this resonates or you want to share your thoughts, please leave a comment on this post. I’d love to hear from you and I respond to everyone!

3 — Share the love. If you know someone who may enjoy reading this, please share it with them.

P.S. If you want to reach me directly, you can respond to this email or message me on Substack Chat.

I savoured this whole essay Jack. Really fluid and beautiful writing.

Modern people are so divorced from the origins of their food, like boneless skinless chicken breasts grow in the grocery store.

I love that you’re bringing awareness to something so simple, so easy to take for granted, but really quite miraculous.

Incredible essay, Jack. This was the reminder we all needed. Thank you.