Mastering the Squat: The 5 Principles of Squatting

Squat with Confidence: Optimize Strength, Minimize Injury Risk, and Avoid Chronic Pain in Exercise and Everyday Movement.

Have you ever doubted your squat form or wondered if you’re squatting correctly?

Every time I squat, these question marks pop into my head. And for good reason.

Proper squat form is critical in both exercise and everyday life.

The squat is one of the five major movement patterns of exercise:

Pull

Push

Squat

Rotate

Hip Hinge

Not only is it a cornerstone of exercise, but other than walking, squatting is the movement we perform the most in a typical day.

Every time you sit, stand or crouch, you are squatting.

Proper squat form helps to build a strong posterior chain and legs while preventing chronic knee and back pain that comes from years of poor technique.

Learning how to squat properly isn’t glamorous or sexy, but it is critical if you want to live pain-free and learn to love squatting.

These principles can be applied to any type of squat (air squat, goblet squat, back squat, etc.) to optimize your performance and, more importantly, prevent injury and chronic pain.

The Five Principles of Squatting

A proper squat is a stable squat.

A stable squat is a powerful and mechanically correct squat.

That means you’re generating maximum torque while minimizing your risk of injury and avoiding chronic pain that stems from repeating a movement with bad form.

Although the following principles are universal, everyone’s squat will look different due to variations in mobility and bodily proportions.

Squat Principle #1: Distribute Your Weight Evenly in the Center of Your Feet

Imagine screwing your feet into the ground with your weight evenly distributed over the centre of your feet, right in front of your ankles.

NOT on your heels.

NOT on the balls of your feet.

NOT on the outsides of your feet.

You were probably told, as I was, to shift your weight into your heels while squatting.

This is commonly taught to prevent squatters that lack mobility or technique from rolling onto the balls of their feet, with their heels often coming off of the ground.

Although shifting your weight into your heels may prevent this specific fault, it can lead to weight-distribution issues and impede your ability to properly perform squats and other movements.

So, focus on centering your weight just in front of your ankles and keeping your entire foot in contact with the ground throughout the movement.

If you do this while rotating the thigh and knee outward, away from the body (aka creating an external rotation from your hips), there should be a solid arch in your foot.

This arch, as opposed to a collapsed arch, lifts the foot just enough to allow the ankle, knee, and hip to stay aligned.

Remember, the goal here is a stable foot and ankle position for the entire movement.

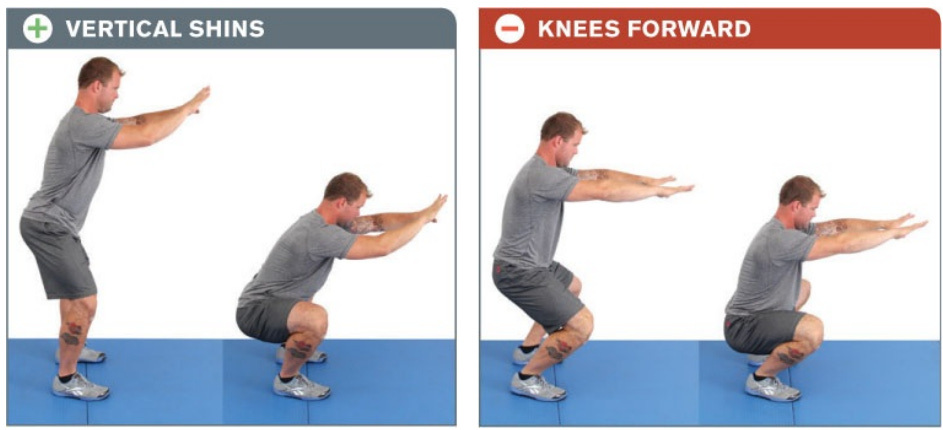

Squat Principle #2: Keep Your Shins as Vertical as Possible

Try to keep your shins as vertical as possible as you drop into and rise out of the squat.

Vertical shins increase your power and unload weight from your knees, decreasing the force on your soft tissues, especially the cartilage, patellar tendon (which attaches the bottom of the kneecap to the top of the shinbone), and ACL ligament.

Your knees will inevitably come forward as you descend, but the goal is to delay this motion for as long as possible.

Then, as you rise out of the squat, think about getting your shins vertical as soon as possible.

Vertical shins will also keep tension in your hips and hamstrings, thus maximizing your power and minimizing flaws in your technique.

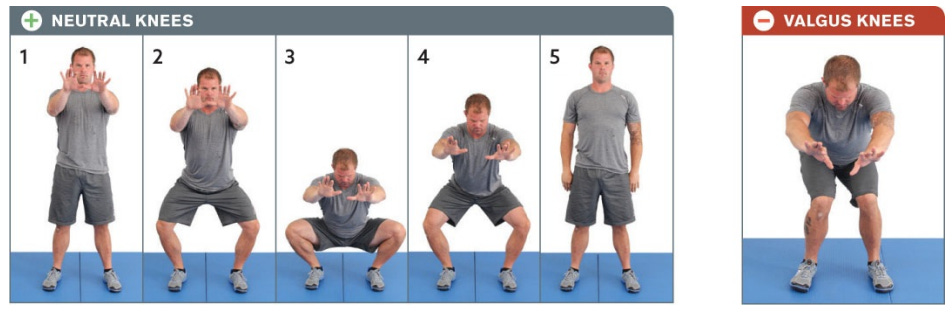

Squat Principle #3: Maintain a Neutral Knee Position

Your knees should remain neutral, meaning they should track up and down along the same vertical path as you descend and rise out of the squat.

The primary driver of squatting-related knee injuries is the knees twisting inward (valgus knee collapse).

To prevent this, remember the cue “drive your knees out.”

Just don’t take this to an extreme where you’re shoving your knees out and rolling onto the outsides of your feet—that violates Squat Principle #1 and can destroy your ankles and knees.

Another widely held squatting belief is that your knees must track directly over your feet for the entire movement.

It is true that your knees will track over your feet if, A) Your feet are turned out and you’re creating external rotation from your hips, B) If you take a wide squat stance, C) If you lack full hip range of motion, or D) Some combination of A, B, and C—all of these are fine.

But if you have full range of motion, are externally rotating from your hips, and your feet are straight or slightly turned out, as shown in the photo above, your knees may track outside of your feet—this is also fine.

It is not okay, however, for your knees to track inside of your feet, as shown in the Valgus Knees image above.

The goal is to limit side-to-side knee movement and prevent your knees from caving in by maintaining a stable and neutral knee position.

This is done by externally rotating from your hips, “screwing your feet into the ground,” and distributing your weight over the centre of your feet.

What does “Drive Your Knees Out” mean?

“Drive your knees out” is a cue to encourage the squatter to stabilize their hips by creating external hip rotation.

An external hip rotation means the thigh and knee are rotating outward, away from the body.

In simple terms, a good squat is one where the ankles, knees, hips, back, and shoulders are all stable.

Cues like “drive your knees out” and “screw your feet into the ground” are designed to help you achieve a stable squat.

Use the knees-out cue as a reminder to create external hip rotation and to prevent your knees from collapsing in.

But do not shove your knees out as hard as possible.

This will cause the squat to feel awkward and can create faults such as rolling onto the outsides of your feet which may lead to serious ankle and knee problems.

You want to create enough torque to match the demands of the movement.

Drive your knees out (i.e., create external hip rotation) just enough to meet and combat the forces trying to pull your knees inward.

This will make the movement feel fluid and minimize injury risk.

Squat Principle #4: Load Your Hips and Hamstrings

Start every squat by loading your hips and hamstrings.

To do so, tilt your torso forward and drive your hamstrings back.

This ensures the right muscle groups are loaded and allows you to hinge from your hips with a neutral spine while maintaining proper torque through your arms and legs.

It fortifies your posture so you don’t break at the lumbar spine (lower back).

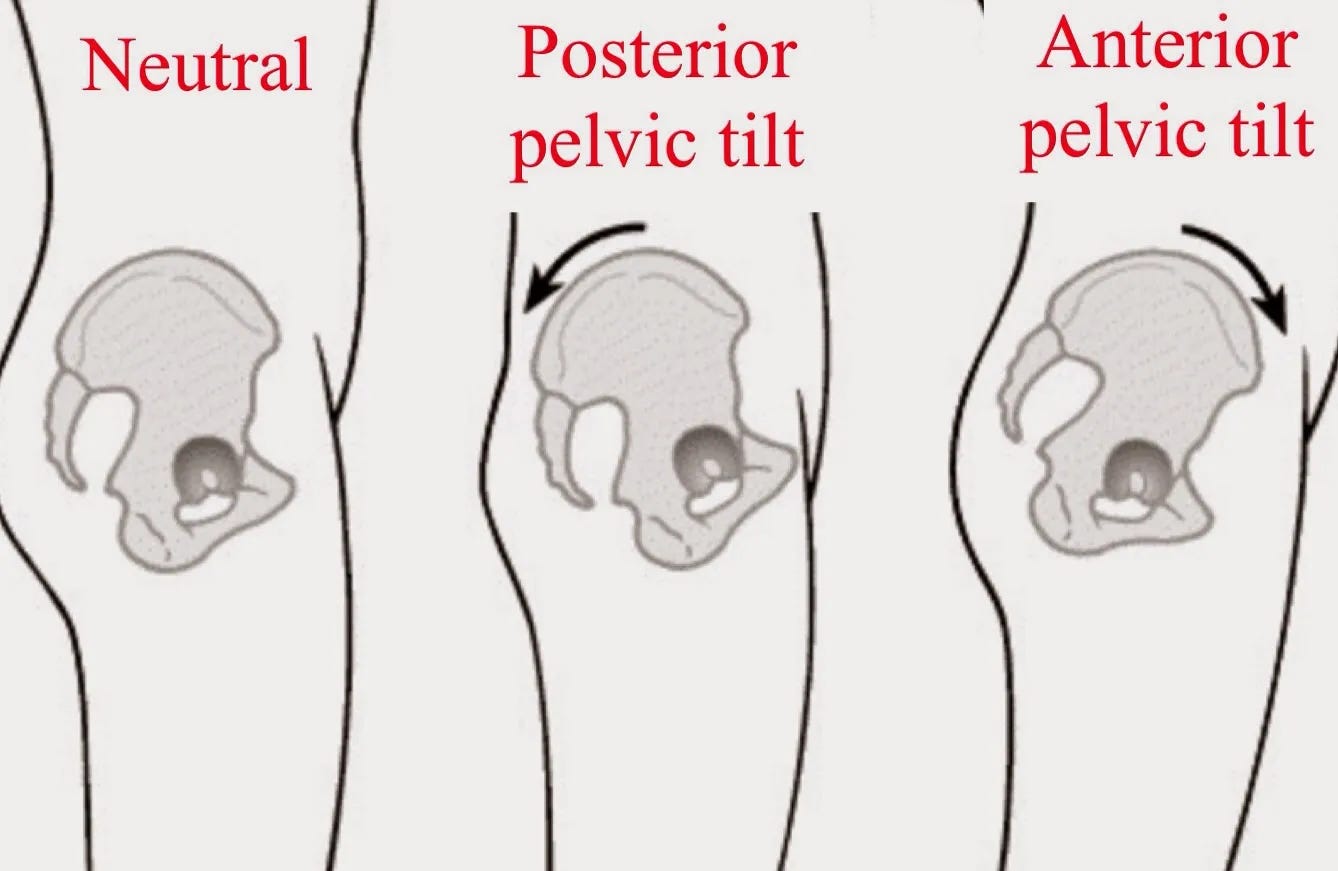

A common mistake is keeping your chest up and reaching your butt back as a way of keeping your shins vertical (Squat Principle #2).

This tends to result in an overextension fault known as an anterior pelvic tilt.

An anterior pelvic tilt is when your pelvis is rotated/tilted forward, which forces your spine to curve.

To avoid this fault, think about sitting your hamstrings back as you initiate the movement.

This will help properly load your hips and hamstrings whereas if you think about reaching your butt back, you’re more likely to end up overextended.

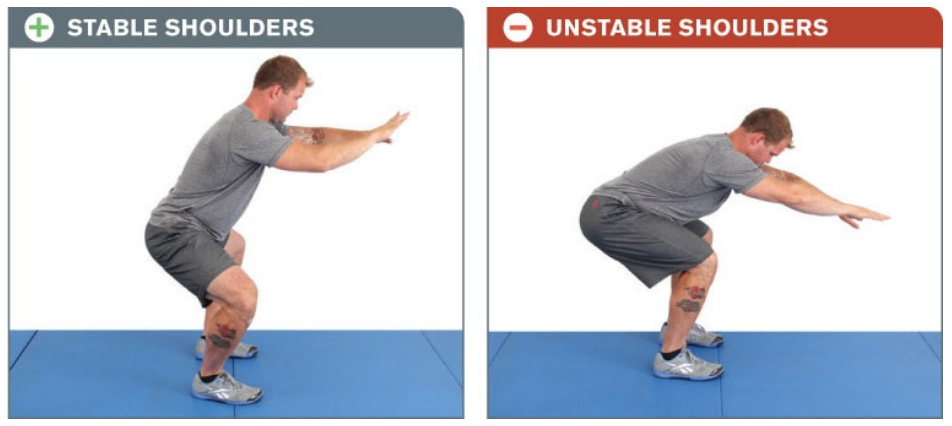

Squat Principle #5: Create Stable Shoulders

Although the position of your arms will vary depending on the type of squat you’re doing, your shoulders should always be set in a stable position by creating force from an external rotation.

An external rotation of the shoulder is the rotation of the upper arm away from the front side of your torso.

The goal is to create tension that will stabilize your shoulders and activate the muscles across your upper back in order to create a braced neutral spine.

If you’re setting up for a bodyweight squat, pull your shoulders back while turning your thumbs toward the inside of your body.

If you’re setting up for a barbell squat, screw your hands into the bar by twisting them—right hand clockwise and left hand counterclockwise—as if you were trying to snap the bar in half.

You want your upper back and shoulders to stay upright, strong, and stable throughout the movement.

The Squat Summary

Keep the following key points in mind the next time you squat:

maintain a neutral spine,

ensure your knees track up and down along the same path,

keep your shins as vertical as possible throughout the movement,

tilt your torso forward and drive your hamstrings back to start the squat,

keep your weight distributed over the centre of your feet (right in front of your ankles), and

create external rotation from your hips—that means the thigh and knee should rotate outward, away from the body.

Remember, squatting—from your feet to your shoulders—is all about stability.

If you don’t feel or look stable, revisit these principles to see where you might be going wrong.

That’s all, folks. Thank you for reading!

Help a friend—If you found this article valuable, please click the ❤️ button on this post so more people can discover it. Beyond that, feel free to share it with someone who would benefit from reading it!

Let’s connect—If you have a question or just want to chat, I’d love to hear from you! Reply to this email, leave a comment, or find me on Twitter.

Much love to you and yours,

Jack Dixon

The Squatting Dictionary

Cue: A verbal indicator that is specific to a particular moment or action.

External rotation: A rotation away from the center of the body.

External rotation (Hips): An external rotation from your hips means the thigh and knee rotate outward, away from the body.

External rotation (Shoulder): An external rotation from your shoulder means your upper arm rotates away from the front side of your torso/centre of your body.

Neutral knee position: While squatting, your knees should remain neutral, meaning that they stay on the same vertical path as you descend and rise out of the squat. In other words, your knees should track up and down along the same plane.

Anterior pelvic tilt: When your pelvis is rotated forward, which forces your spine to curve. Generally caused by excessive sitting without enough counteractive exercise and stretching.

Posterior pelvic tilt: When the front of the pelvis rises and the back of the pelvis drops, while the pelvis rotates upwards. Generally caused by an imbalance between the core muscles and the leg muscles and results in a variety of uncomfortable symptoms, such as tight hamstrings and back pain.