As you read this, my brother is probably rolling up our tent on the soft forest floor as I stir a shaky pot of oats on a burner that can fit in the palm of my hand. We’re two nights into a three-night backcountry hiking trip in Algonquin Provincial Park, a vast interior of maple hills, rocky ridges, and thousands of lakes three hours north of Toronto.

We’re probably cold, wet, and tired of being blitzed by bugs. But life is simple here. No to-do lists. No distractions. No expectations. Nothing to do all day but survive. Tear down camp, eat, walk, eat some more, set up camp, sleep. Our work is interluded by the long, thoughtful conversations we always find ourselves in. If they come, periods of silence between us are short. There will never be enough time to say everything that has to be said.

The urge to be more productive and efficient and effective follows us into the forest. There is never anything else to do here other than exactly what we’re doing but still, slowing down doesn’t come easily. The work that needs to be done is defined and limited. Unlike life at home, there is no ever-expanding to-do list. Once we do what needs doing, we are done. When there’s less to do and everything is vital, our energy can be channelled into slowly doing things right: set up camp and kitchen perfectly, hoist our food bags high between two trees, and redo our work when we need to. There’s no rush: walk slowly, stop often, and judge time by the sun in the sky not the clock on my wrist.

Our new environment is teaching us. Remoulding us as we need to be. To listen for running water to fill our canteens. To pay attention to sounds in the forest that might be a bear with its cubs or a moose with its head down. To navigate with slow precision or risk being irreversibly lost. On our first day, squirrels in our side view scampering up saplings sent our pulse skyrocketing. Now three days in, we’ve stopped reacting and started to listen. Our nervous systems, groggily waking up from a thousand years dormant, warily realize that this is where they were born. The forest slowly reminds us that what we value in the modern world—always moving faster with an insatiable need to do more—will get us killed out here.

To those who don’t understand, I can never fully articulate why I want to be here, subjecting myself to a quality of life that we supposedly escaped hundreds, maybe thousands, of years ago. If the stuff we’re constantly being sold—products and services that offer convenience and ease and immediacy and pleasure—are supposed to make life so much better, why do I feel pulled into the woods to live as harshly as our ancestors did? Why am I sitting on a log shivering over a bowl of bland oats when I could be cozily lying on my couch with Uber Eats on the way as I scroll Instagram with Netflix playing in the background?

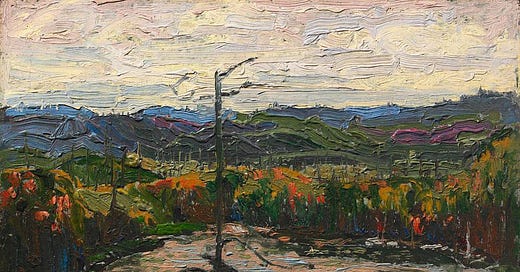

Like water flowing down the deepest gully, I am shaped by what I come into contact with. My environment irresistibly forms me. Maybe I’m here not for what this place offers but for all it doesn’t. No opinions or reception or email. No skyscrapers or traffic or billboards.

Out here my surroundings rival modernity in all that they demand—presence, sacredness, unhurriedness—as how I experience time inches closer to my ideal. My shoulders drop. I relax. Something deep within me that slumbers through modern life rustles awake out here.

My time among the trees is ending soon but the calm slowness the forest nudged awake within me will last until the whirlwind of life knocks that part of me dormant again.

And when it does, I’ll return to the woods.

What I’ve been up to:

Last weekend, I volunteered as a Finish Line Marshal at the Toronto Marathon as my sister completed her first full marathon and my mom ran her third half in less than 12 months.

This Monday, I had an in-person job interview then left Tuesday morning for a backcountry hiking trip in Algonquin Provincial Park with my brother, where I am right now.

I emerge from the forest on Friday, volunteer at and run the Spartan Race on Saturday with my girlfriend, friends, and brother, and then have to prepare for another job interview on Monday. Life is moving!

Thanks to my friend

from for your immensely kind and helpful edits on the initial drafts of this post.Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this post, please let me know…

1 — Leave a like. I’d be grateful if you’d consider tapping the “heart” ❤️ at the top or bottom of this page.

2 — Get in touch. If this resonates or you want to share your thoughts, please leave a comment on this post. I’d love to hear from you and I respond to everyone!

3 — Spread the love. If you know someone who may enjoy reading this, please share it with them.

Lots of love,

Jack

P.S. If you want to reach me directly, you can respond to this email or message me on Substack Chat.

I agree with Rick, this is a stunner. It makes me so happy to know that you and Tommy were actually out in the woods when this went live. This piece is magic.

As I mentioned to you, this makes me want to get back out camping as soon as possible. You've really captured here what being in the woods does for a person. I sure hope this trip was a great, restorative one. Here's hoping you post a follow-up! 🌲

For me this is one of your best pieces I've read Jack. Just beautiful. "Our nervous systems, groggily waking up from a thousand years dormant, warily realize that this is where they were born." That sentence so artfully describes the feeling of being in the forest, and your words come from roots that are deep enough to reach me, even here next to the billboards.